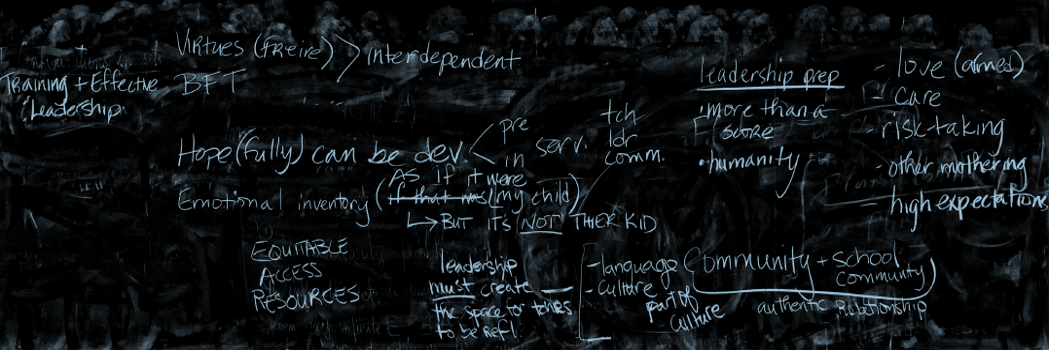

My immediate response to all of the articles this week examining the counternarratives of, and more broadly, the role of Black Feminist/Womanist caring among Black women educational leaders is– who is showing the same radical care to them?!! How are they navigating and finding care for themselves in the same dehumanizing spaces as their students/children? Amidst enacting critical care in schools, Wilson (2015) draws the connection between critical care and transformative leadership in listening to the counter narratives pf Principal Simms, also an African American woman, in confronting and engaging in systemic critique of the poverty context of the community through instilling a school leadership force principled in care and embodying compassion with parents and students. Beauboeuf-Lofontant (200) identifies the themes of the maternal, political clarity, and an ethic of risk in the womanist caring of Black women educator. The maternal care that Black Feminist caring teaching enacted was rooted not in the individual relationship with men and children, but rather emerged from the sense of mothering as a communal responsibility (Bass, 2012; Wilson, 2015). This embodiment of critical care holds political clarity in the recognition of interlocking, intersectional, systems of oppression and injustices that implicate society and education simultaneously, and is rooted in the ethics of risk that there lies an interdependence in the creation of fairness and justice rooted in an understanding that the “self is part of rather than apart from other people” (p.81). Withserspoon & Arnold (2010) extend such themes of womanist caring in the conceptualization of care in a theological/religio-spritual sense. I was intrigued by the account presented in Bass (2012) of care triumphing justice- the teacher who shares her decision to not implicate a student for the possession of weed and instead express an enormity of care that place her own self at risk. It is this risk and also the radical empathy and care that Womanist educators, as in this narrative, the begs the question of WHO is showing radical care to the “care-ers”, or ones enacting the care? Of course, this is not a one-directional process, but the responsibility of care of course holds risks and implications for Black feminist educational leaders themselves. But how does/can the system or settings of schools treat womanist/black feminist educational leaders better? Who is healing our healers? How can we enact the same critical care towards Womanist educators, specifically Black women in educational leadership positions?

Radical Care Sp21

Teaching & Leading for Justice in Schools

Sohini, POWERFUL questions!

And in thinking about your questions I was powerfully reminded of the following quote by Malcolm X (1962) “The most disrespected person in America is the Black woman. The most unprotected person in America is the Black woman. The most neglected person in America is the Black woman.”

I struggle with the feeling of accepting the narrative of the strong Black woman and/or pushing back against it. #It’sTheTensionForMe. It feels like, throughout history, those who have been the backbone of society in various capacities have always served as the “sacrificial lamb” that gets battered and abused for the betterment of others. How do we reconcile those feelings? In any event, thank you for your post!