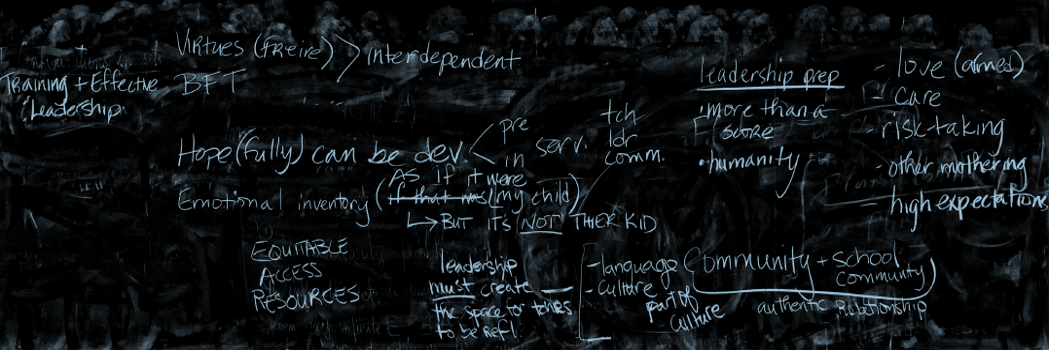

So while we can hyperfocus on Social justice youth development models (Cammorota, 2011), or healing as a catalyst for social and civic change (Ginwright, 2011), or critical and audacious hope (Duncan-Andrade, 2009), but we can’t meaningfully discuss any of these types of hope without hyper-focusing on relationship building. All of this relationship building is made meaningful and impactful when focused on humanity and dignity. Learning to SEE people for who they are and understand how they make meaning in their lives through taking part in and sharing or repressing their stories through various modes. This work for educators, particularly those who come from mismatched communities from the ones in which they serve, involves becoming involved in the lives and communities of students they are serving. This work entails decolonizing their racial and socioeconomic epistemologies that create “epistemic violence” (Dotson, 2014) by, for example, framing some forms of social capital as more desirable than others.

Care starts with honoring people’s humanity, not seeing them as outside of our “spheres of obligations” (Wynters, 1994). Teachers need to create space where they see what cultural, political, social, and personal assets that ALL students bring to the classroom, and find space to highlight and center the various class assets. As referenced, students are a part of the class garden, and removing an element destroys the class ecosystem. The garden needs to show why each element is important to the ecosystem and how it supports a balance in the community. By being a social justice educator and including the lived experiences of students, educators create space to SEE students and identify their assets so those assets can be centered in classroom contexts that reveal community knowledge to be just as if not more important than academic knowledge.