The readings this week definitely left me with mixed feelings and some questions. First, Yosso’s notion of community cultural wealth I feel is an important response to Bourdieu’s theory of “cultural capital” which has been used (or mis-used) in many cases to justify deficit beliefs about communities of color and to support the notion that they need “fixing” in order to better “fit” into capitalist society. A response to this theory or the mis-use of this theory is important. However, as my classmate’s have mentioned, placing the “community cultural wealth” into a similar paradigm as “cultural capital” similarly seems to reduce the humanity of communities of color to six categories of wealth, which still suggests that outside of these categories there is deficiency. It almost seems to reduce the inherent wealth and value of being human and makes it seem as though that needs justification and isn’t enough. I love Sohini’s connection to Audre Lorde’s words: “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” and agree that the framework of community cultural wealth seems to be born out of the same foundation (capitalism) as cultural wealth, and while they exist on different ends of the spectrum, they are still on the same spectrum. I wonder what it would be like to rebuild the entire house on a completely different foundation, where we wouldn’t need to justify or describe wealth because it was so clear and evident because our society was in touch with our humanity and the humanity of others. While that’s said, I do think there are some important contributions to the field that come from this piece. For example, Yosso claims that “CRT shifts the research lens away from a deficit view of Communities of Color as places full of cultural poverty disadvantages, and instead focuses on and learns from the array of cultural knowledge, skills, abilities and contacts possessed by socially marginalized groups that often go unrecognized and unacknowledged… CRT centers the research, pedagogy, and policy lens on Communities of Color and calls into question White middle class communities as the standard by which all others are judged (Yosso).” Acknowledging this shift in focus and redefining the “standards” that we use as a society to judge communities based on the white middle class is an important acknowledgment, and the six forms of capital help to shift the focus away from what’s wrong to all of the things that are right. However, I think in the new house that we build, we won’t have to justify or clarify one’s capital as being worthy because being human will be enough.

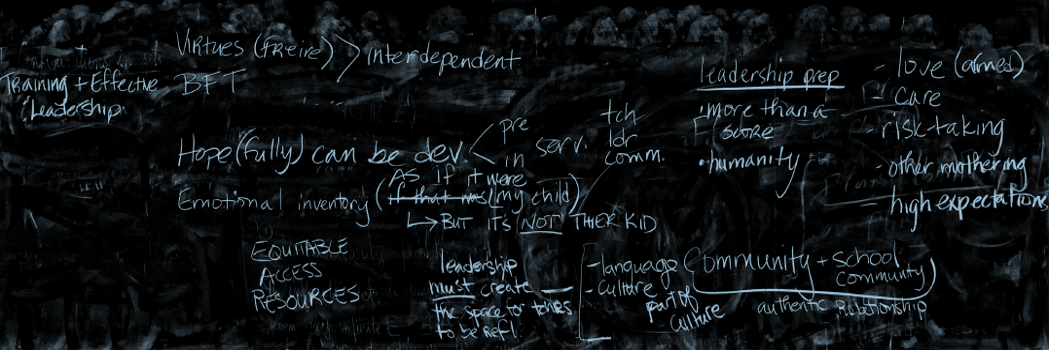

The second reading this week was an excellent case study of school leadership. One quote that stood out to me was: “Just because we work for the whole, not the I, does not mean that our leadership is less important. At times, it is even more important. You can sound like you know everything, look so well put together and know nothing. That is the “I” culture, but this work is about relationships, this work is about people, this work is about kids” (Rodela & Rodriguez-Mojic). To me, this quote points to the most important aspect of leadership: relationships and dialogue. It made me think a lot about Freire’s approach to leadership, where the leader is in constant dialogue and continuously learning from those who she leads. Putting kids at the center and working in relationship with the school community is the only way to lead a school in a transformational way. While reading about the principals gave me a lot of hope, seeing the statistics on the number of Latinx school leaders compared to white leaders was disheartening and left me wondering about what next? Where do we go from here? How do we flip these numbers on their head? Why are these numbers so small? It made me think back to our readings about the history of Brown and the shift in leadership from leaders or color to predominantly white leaders and teachers in schools and it made me question what needs to be done to return to a community school model in which the school is led by community leaders that look like their students. This might also require rebuilding the house…