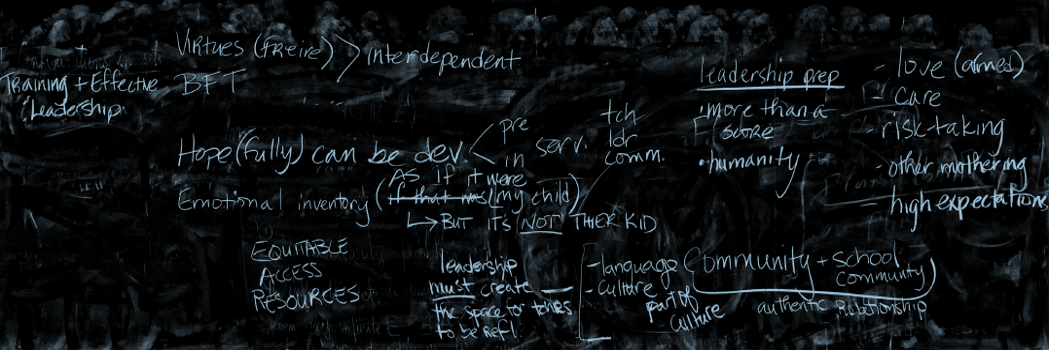

This week’s readings helped me to appreciate the many ways in which critical care shows up in our schools through black women teachers and leaders. I loved unpacking the concept of mothering and motherhood in schooling and how a woman’s natural inclination towards mothering and parenting can and should inform their teaching. In the Beauboeuf-Lafontant article, she mentions the ways in which mothering for many black women educators is “a matter of fact” and an “emotional strength.” It was powerful to read these words alongside the concept of mothering because so often in our capitalist society, the act of “mothering” is looked down upon and perhaps even seen as weak. This article flips this notion on its head and instead places motherhood in highest esteem, as something that comes natural to women and that is a key in our collective liberation.

Beauboeuf-Lafontant also likens care and love in teaching to the bible and the ten commandments, stating, “Thou shalt love they students as you would love your own children” (Collins, 1992, p. 178). This statement speaks to me deeply and makes so much sense, yet I have been in so many classrooms where there feels to be a void of love, or rather, a lack of focus on love and care. We forget that we are working with human beings and that human beings need care in order to grow and thrive. A connection to religion was also discussed in the Witherspoon and Makoto Arnold article, who discussed the ways in which theological caretakers exhibit care. It made me wonder about our “secular” public education system which is so often void of spirituality and if spirituality and spaces of worship can actually teach us a lot about critical care. The exploration of “The Black Church” in the article sheds light on the ways in which Black spirituality has come to be located in resistance. It also sheds light on the ways in which black women educators resemble pastors. This connection to spirituality is profound and necessary (Witherspoon, 2010). Similar to mothering, spirituality comes naturally. In our secularized world, however, it has been looked down upon and even discouraged in public schools. Placing spirituality and a spiritual practice in the center of teaching practices places care at the center. “Much like a pastor, these women not only believed in ensuring the academic well-being of their students, but also in providing holistic care of mind, body, and spirit” (p. 224). This holistic approach to education is necessary. I am left wondering: Why have we lost this approach in so many classrooms, and how can we regain it? How can we better care for ourselves so that we can focus on our students and care for them as we care for our own children? How can we foster our own spiritual development so that we can also foster it in our students?