Guiding Questions:

- In what immediate ways can care transform the classroom for both students and teachers?

- What does care look like in a school system driven by capitalism? Can those even coexist?

- How can care shift from an individual act/practice to a collective project?

Focus: I am interested in deepening my critique and analysis of the ways that “soft” care (Rivera-McCutchen, 2012; Curry, 2016;), problematic White feminist notions of caring (Katz, 1999), and damage-framed (Tuck, 2009) pedagogy play out at the school where I teach, in my own teaching practice, and in the culture of my school. I also want to find ways to center student voices in the conversations we have at my school and in the decisions that the teachers, staff, and administrators make in seeking to push our school to embody authentic, “critical care” (Rivera-McCutchen, 2012; Curry, 2016).

Unessay: One of the central spaces where students and teachers have the opportunity to build caring relationships is in “crew” – an advisory program where one teacher and between 8 and 15 students meet every day for 30 minutes for a two year loop. I am a junior-senior crew advisor, and have been with my current crew for the past two years. As part of the senior experience, my students have reflected on how the school has shaped them and how they have shaped the school in multiple spaces, including their final “student-led” family conferences, as part of their final expedition (our school’s term for the interdisciplinary approach to learning that uses a common guiding question and set of objectives to frame the learning that happens in each class to build towards an interdisciplinary final project), Legacy, and as part of their final project for English, “Final Words,” where they give a speech to the people who know them best about their growth and learning. Although these are all powerful spaces of reflection for students, our school has no real pathway for students’ reflections, expertise, and voice to be centered in the decisions we make as a school. And in my conversations with students over the years, this has been their greatest source of frustration with the school, heightening feelings of not being seen, heard, validated, or respected.

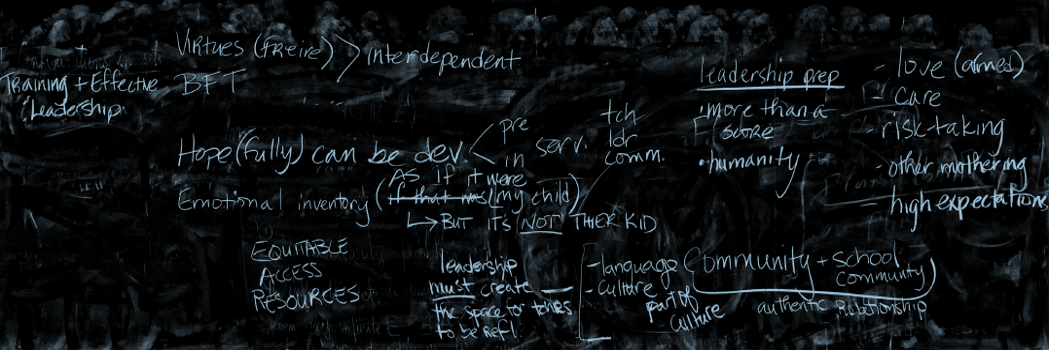

I wanted to build more space to center student voices in the work that senior crew advisors and teachers were doing to create experiences for students. I spoke to the other seven senior crew advisors, and asked if we could implement some common lessons that talked explicitly about care in ways that built on the senior reflections happening in other spaces. I created a set of three lessons, with feedback from several other advisors, that all senior students engaged with during the first two weeks of May. The purpose of the lessons was to build a framework for students to talk about their own understanding and experience with care, and to build towards sharing their expertise about how our school does and does not embody critical care. We began by establishing some common language about care, both authentic and care and “problematic” care. Then students began describing moments and spaces in school where they had experienced those different kinds of care. The final lesson opened up space to begin evaluating the core aspects of our school in terms of how well they aligned to our understanding of authentic and problematic care. Some conversations led to project ideas from students who want to share their feedback with the school in different capacities (including their Final Words, and joining the final teacher meetings of the year). Students captured their thinking in a series of Jamboards, which they got to choose to either keep private or share with the other crew advisors.

As a crew team, we came together after implementing the lessons to share our experiences and document some themes that emerged. Many of the advisors shared that the conversations were some of the most animated that they had seen in a long time, and that students seemed really energized to have a space to talk about care. We discussed how we might better align all three of the opportunities for student reflection during senior year (SLCs, the Legacy expedition, and Final Words) in a way that would expand student voice and offer opportunities for students to share their wisdom and vision for making our school better that could have real, material outcomes. We are hopeful that we might be able to expand the initial three lessons to build out a more robust crew curriculum for seniors that could support this process, and also build on the proposals of students to join teacher teams when they make decisions, offer feedback about key aspects of the school (school policy, school traditions and rites of passage), and have more space to actively shape the direction of the school as a whole.