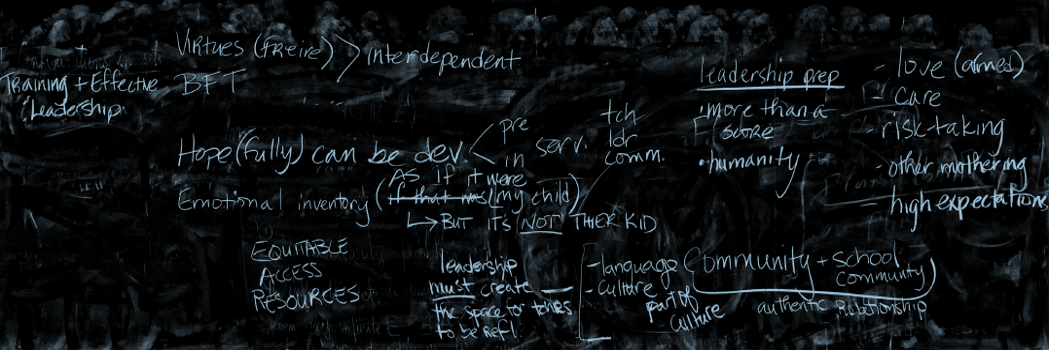

I really enjoyed this week’s readings, both because of their hopefulness and openness, and also because they engaged so many concepts that are often explicitly omitted or erased from the discourse about teaching and school reform – love, faith, and political action. Each author built from Freire’s initial teaching to consider what it could mean to purposefully reenter those concepts to fundamentally transform the discourse.

In thinking about the role of political action, or “armed love” as named by Freire and Rivera-McCutchen, I thought about the common practice of telling teachers (and administrators) that they must be “apolitical,” or “neutral” in the classroom. These calls to be “apolitical” are in reality calls for teachers to adhere to a very specific kind of politics. The notion that it is possible to be apolitical (or neutral) is a political stance, and one that serves the interests of an oppressive school system (and by extension, the violent settler colonial logics that the school system upholds) – a stance that is easier for teachers and administrators who do not see their own humanity bound up in the liberation of all from oppression. As Rivera-McCutchen notes, “neutrality in the face of injustice, and particularly racial injustice, is unethical” (p. 244).

Freire directly addresses the question of a teacher’s position as a political agent in his discussions about fear and courage. As he explains, “to the extent that I recognize that though an educator I am also a political agent, I can better understand why I fear and realize how far we still have to go to improve our democracy.” His identity as a political agent is tied up with the notion of “armed love” – “the fighting love of those convinced of the right and the duty to fight, to denounce, and to announce”. Similarly, as Miller at el note, “Freire’s baseline discussions of love, humility, faith, hope, and solidarity … reintroduce language core to the human condition but foreign to the contemporary discourse on educational change” (p. 1091). This quote made me think about what Sohini wrote about and shared in the chat during class – that the violence of whiteness and settler colonial logics severs us from our innate human tendencies toward empathy and care, love and connection.

And so the public school system in our country, which was hijacked and designed as a technology to uphold white settler colonial logics, necessarily needs to function to perpetuate the severing of those ties to our innate humanness – as political beings, as loving and complex beings, as relational and empathic beings – because settler colonial logics requires dehumanization, and the false definition of humanness based in ownership and domination. The readings work together to show what it might look like to build a vision of schools, and larger communities, that are deeply connected to humanity in ways that seek to dismantle oppression, collectively.

Hey Lucy, thank you for this thoughtful reflection and for connecting it back to Sohini’s thoughts last week. Like you, I’m a teacher and my work has been primarily within school walls. Now, your analysis of schools, “designed as a technology to uphold white settler colonial logics, necessarily needs to function to perpetuate the severing of those ties to our innate humanness” leaves me further convinced that we as teachers and school leaders can aid in the effort to decolonize our schools but that this work demands learning from, listening to, and working alongside the community. To move past the shallow calls for dialogue in our current schools towards dialogical love (Miller et al., p. 1082).

Your entry made me think about all that Principal Bloomberg accomplished (Rivera-McCutchen, 2019) and to imagine: What more becomes possible when a school leader’s armed-love joins hands with a community’s vision and strategic plan for change? I recently spoke to 2 parents in district 15, one who said that this was the only school they did not apply to, because of the metal detectors, and another parent who said they applied, even though they have those metal detectors and that they hope to help get rid of them. Imagine how many other parents and community leaders feel these same concerns. And how unshackled these community members are, in their ability to confront and form a united effort against this and other dehumanizing DOE policies. This brings me back to Freire’s call that we form strong alliances in our work. I see so many groups operating on their own, or forming small alliances, between parents, community leaders, teachers, and school leaders, but what happens when a united effort at humanizing education for all is formed? An effort where all contribute and make transparent their unique contributions, limitations, fears, courage, and areas of expertise in this work.

Thank you!

Mariatere