Radical Mapping to Locate Critical Hope, Love, and Care

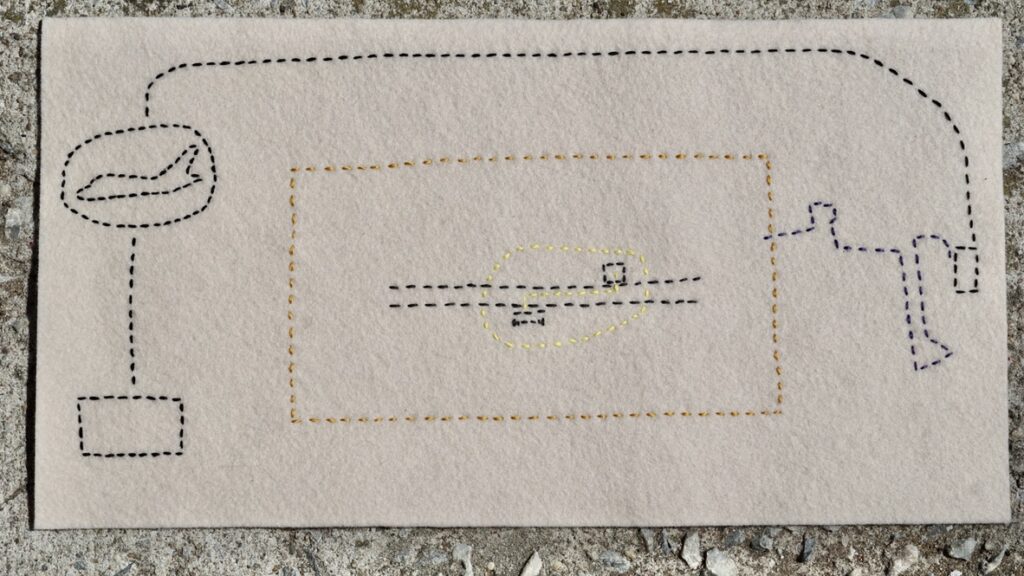

map-poem #10: Mapping to Disrupt Racist Policies and Practices Inside and Outside of Schools (Burlington, VT , 7/26/19)

Keywords and colors: travel from JFK to Burlington International Airport (black), purple bus line (purple), Church Street Marketplace (mustard), street, coffee shop, and bench (gray), disrupting injustice (yellow)

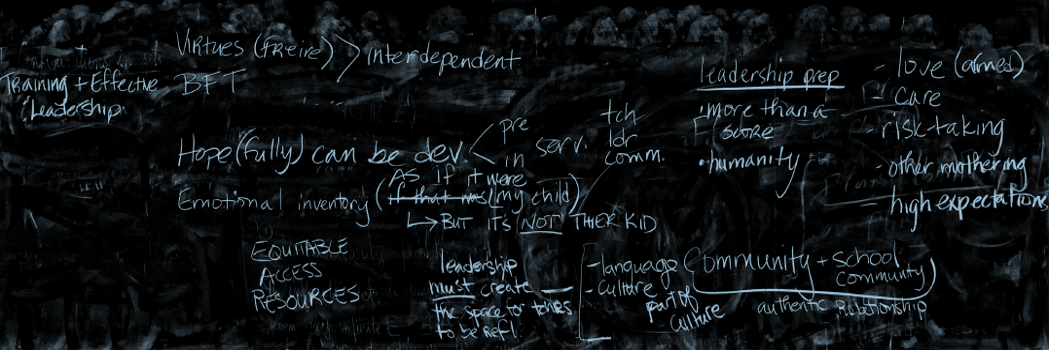

Self-Reflection: How can we use art to increase critical consciousness, hope, and collaborative action in our schools and communities?

Collective Action: Later this month, I will co-facilitate a map making workshop with a group of teachers, staff, and administrators who form part of anti-racist professional learning communities (PLCs) in one school district in Vermont. Aimee, the facilitator of these groups, explained that participants gather to examine their own identities, positionality, and teaching practices as they strengthen their own skills and understanding as anti-racist educators. The educators in this group self-identify as white, which is in line with the general population of this area whose racial composition is 96% white. During this workshop, I will share map-poem #10 to talk about calling out and disrupting racial injustice.

As an arts-based inquiry, participants will have the opportunity to engage in critical map making of their own to locate “brave or safe-enough” spaces in their communities. In this context, brave spaces, understood as spaces where one feels “safe enough” to intervene and take action to disrupt racist policies, practices, and actions inside and outside of schools. Then, to use these maps to share their stories and plans for next steps. This engagement with art and mapmaking as tools for doing anti-racist work will lead into a broader discussion of all of the factors, resources, and conditions that make this work possible beyond these PLCs. Our hope is that we will walk away from this session with a new understanding of how art and critical map making can serve as tools for increasing hope, love, and care by helping us surface and share our transformative stories and plans for action.