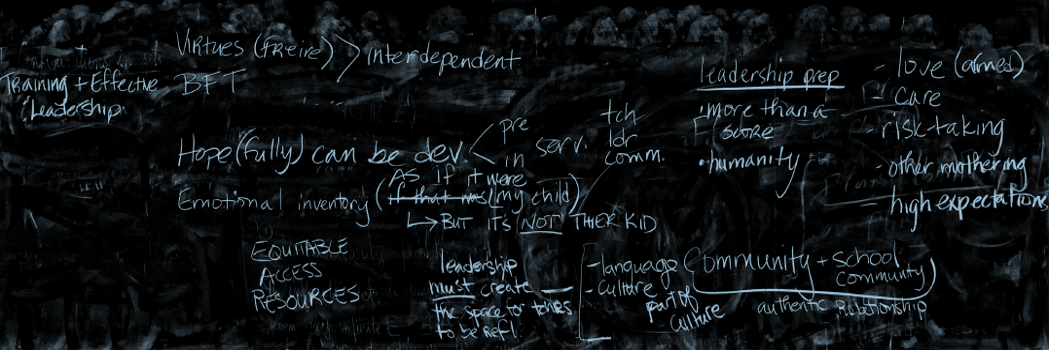

This week’s readings reminded me of my long and patient relationship with Freire’s work. I was in my late teens when I first tried reading Pedagogy of the Oppressed. I remember feeling drawn to these concepts but overwhelmed. Although I’ve taken long breaks in between, I have never stopped coming back to his work, looking for new messages, strategies, strength, and hope. Along the way, I committed some of the mistakes that this week’s authors brought up, thinking that somehow, we should apply his methodologies to our current context. As Miller et al. notes, Freire has created a language, a set of categories and practices that we should not attempt to replicate but take what is useful to guide our own analysis and to use within our own educational contexts (p. 1087).

The authors this week helped me hear new ideas in his work. Miller et al.’s challenge that this work requires that we explore alternative actors and venues has stayed with me. That teachers and school leaders alone cannot do this work. That we need to see how our ties to schools constrict us. To examine how they limit how far we can go in our critique of the system, because of our fear of the repercussions. While community activists operating within their own communities benefit from their independence. As the authors explain, “Here institutional detachment (primarily from schools) emboldens liberal critiques of oppressive regimes” (p. 1088). This article made me think about the role community centers have played in strengthening Black communities. The type of centers and programs that Dr. Bettina Love (2019) credits with helping her to become more critical and thrive growing up. Spaces that were run by people from within the community, who were deeply embedded, knew the families, and cared for the youth. This feels so different from some of the community centers near me that feel more “outside businesses” than transformative. I keep thinking about the idea of community centers as likely sites for radical social change.

I’ll return to the topic of fear because it seems so vital. While this is something Freire directly addresses in his (2005) Letters to those who dare teach, reminding us that our courage cannot exist without it, Darder (2002) does a beautiful job exploring this relationship between our revolutionary dreams, fear, and courage. Fear as a signal that we are doing the work of disrupting the status quo. As a necessary and inevitable of this work, “The more you recognize your fear as a consequence of your attempt to practice your dream, the more you learn how to put into practice your dream” (p. 499). This brings me to the deep care and advocacy work taken principals in Rivera-McCutchen’s (2019) article on armed-love. While we see the courage required for them to challenge racial inequality they were witnessing in their schools, I now want to hear more. To become better armed in love by understanding how they worked with the fears that must have accompanied their courage in their fight for justice.

Mariatere,

I also share in many of the reactions that you wrote about in this week’s reading. The idea of connecting Frierian ideas to community centers also made me think about the revolutionary potential of these alternative educational sites. I also know that these sites come with their own set of issues, such as funding or space. Creating connections between traditional and non-traditional spaces might serve to add more care to schools and deliver necessary resources to communities. These connections, though, must be closely monitored so that they are built on true reciprocity and respect.

I love the idea of community centers as sites for radical change. So based upon that idea and the works, I wonder how can schools themselves become transformative community centers? Like, is it possible, or do the neoliberal, legal, educational, and communal interests conflict in ways that deter solidarity and collective action?

Then, when thinking about fear and courage, I keep coming back to the question: how do we get people from mismatched communities to the ones they serve to show courage when many of them fear displacing their social, economic, and political security?

Dear Mariatere: Like Kushya and Jordan, I want to comment on your thoughts about the potential role of community centers–the kind that have deep roots in their communities as well as leadership from those communities. When I worked at Children’s Aid, I saw some of those centers in action–the Dunleavy Millbank Center in Harlem and another in East Harlem, both of which had decades of experience in their neighborhoods and both of which were run by men of color who had grown up in the neighborhoods and participated in their respective centers’ programs as young people. All that sounds good, no? But those centers were always so fragile in the non-profit ecosystem of New York City, and the pressure on them increased exponentially as the neoliberal philosophy of “if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it” took over in the funding and board leadership community. These two centers managed to survive by cobbling categorical funding together to support their comprehensive programming, but it wasn’t easy. An excellent analysis of this set of challenges is explored in Bianca Baldridge’s book entitled Reclaiming Community: Race and the Uncertain Future of Youth Work. Thanks so much for provoking all this dialogue!